At the Berlin Africa Conference in 1884/85, the 13 European conference members and the USA promised the Belgian King Leopold II the Congo Basin as a prime example of a supposedly “modern” colony. No representative of the affected area in Central Africa was present. Supposedly “modern” was the designation as (African) “free state”, accompanied by some attributes mentioned in the public final act (Acte Général): the slave repatriation from America, the fight against the Arab-continental slave trade or the description as a neutral free trade zone under freedom of customs and shipping, which should not exclude the indigenous population either.

The real intention of this summit was the joint – i.e. largely European – decision on a economic “utilization” of populated areas. A project whose success the participants sought to ensure among themselves by means of a set of rules for preventive conflict avoidance. However, the Acte Général produced more grey areas than rules: However, the Acte Général produced more grey areas than rules: Articles 34 and 35, for example, which defined the form of territorial occupation, were actually limited to the African coastal areas, but legitimised a pan-African push to “divide the earth” (the title of a newspaper article at the time) and in a few years led to the so-called “Berlin borders”, which in their “artificiality and screaming illogicality” (Wole Soyinka) still determine the nation-state borders today.

At the same time, the (intended) absence of any kind of control of the “modern” regulations gave a real carte blanche, which in parts of the African continent led to practices of resource exploitation and forced labor. Whether the Acte Général is to be regarded as historical international law (a then exclusive circle of actors) is not clear today. It is therefore a topical question whether claims for reparations for genocidal crimes in the wake of this conference can refer to formulations in it according to the temporary application of law.

The edition is part of a more comprehensive series of images that trace an arc from the conference to the current compensation claim of the “Herero People’s Reparations Corporation” (HPRC) from 2001 against the Federal Republic of Germany (as the legal successor state of the German Empire) and two German companies. The background of this lawsuit is the historically documented genocidal war of annihilation against the Herero people 100 years ago in today’s Namibia, then German Southwest.

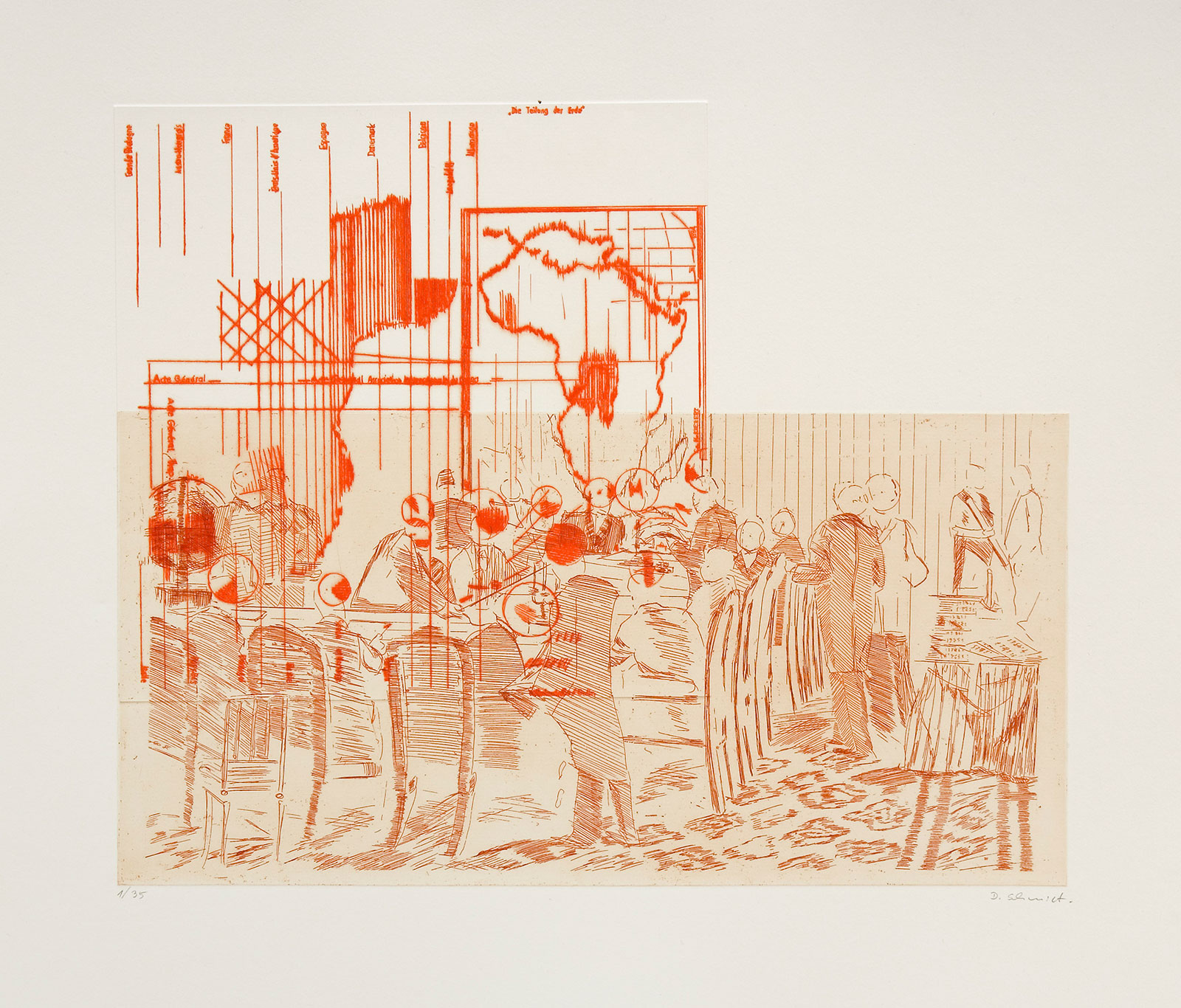

The two-colour copperplate engraving is based on a newspaper illustration from 1884, a representative image in the sense of the common statesman/woman photos known from today’s G8 summits, for example. This copper-coloured quoted 19th century table society is “overprinted” with the “pattern“, the “cuts” and the “projections” of the supposedly universal legalistic speech of this conference.

Text: Dierk Schmidt